- Home

- Joel Bernard

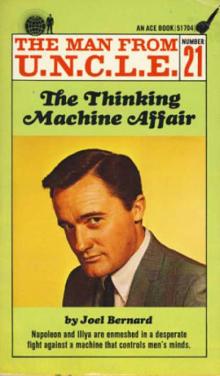

The Thinking Machine Affair Page 4

The Thinking Machine Affair Read online

Page 4

"I must report failure as far as U.N.C.L.E.'S external communications system is concerned. The reason for the failure is my own carelessness and I am ready to accept appropriate punishment.

"When I affixed the last electronic beam receiver on the intercom cable at point G and prepared to fix the remaining eight beam receivers on the external communications system, I overlooked the fact that I must not pass any of the points at which I'd affixed the beam receivers because, as the Head of the Technical Department had warned me, the beam receivers on my body would create an ultra-force and set off the alarms. This is what happened. As I passed point H where I had placed the beam receiver, the alarm went and I was trapped in a steel door pocket which seemed to come from nowhere. I took the living death drug phial and a few minutes later my mind went blank.

"That is all I can report on my partly-successful 'Operation U.N.C.L.E. Headquarters'. But before I took the phial and lost consciousness, I hid the unused electronic beam receivers in the hollowed-out heels of my shoes. I believe the U.N.C.L.E. investigators did not find the beam receivers in my shoe heels when they searched my body.

"That's my report, sir, and I am ready to submit to any punishment the Disciplinary Committee may impose upon me for having only partly carried out my task."

Clive Hughes continued to pretend he was the THRUSH European Center's Chief Organizing Officer. "I want you to describe the exact locations where you affixed the electronic beam receivers so that I can check the chart and ascertain whether 'Operation U.N.C.L.E. Headquarters' was indeed carried out to our full satisfaction," he said.

The hypnotized man described the location of the various gadgets he had planted, and this information was passed on to the technical team so that they could check whether any of the dangerous receivers had been missed. It was soon confirmed that all the gadgets had been discovered and removed by the search team even before their exact locations had been disclosed.

In the role of THRUSH'S Chief Organizing Officer, Hughes asked: "Are you satisfied that the U.N.C.L.E.'S internal communications system is now ready to receive and pass on effectively any transmission from European Center E that is beamed to the receivers you affixed?"

"Yes, sir, definitely."

"You are very confident, but have you taken into consideration the sort of transmissions U.N.C.L.E. Headquarters are to receive?" Hughes wanted to extract as much information from the hypnotized man as possible.

"Well, sir, I don't know much about it. I only know what the Head of the Technical Department told me, which is that the Professor's apparatus is to be linked with an electronic transmitter beamed at the electronic beam receivers at U.N.C.L.E.'S internal and external communications systems. I'm afraid that's all the Head of the Technical Department told me, sir."

"You seem to have forgotten the Professor's name," suggested Hughes.

"Oh no, sir. It's Professor Novak."

The interrogation continued, but it was soon clear that the man had been drained dry of all he knew.

After Clive Hughes had conditioned the man's mind to permanently forget his awakening moments and only remember the happenings that had occurred before he took the phial and lost consciousness, he ordered him to fall into a deep sleep.

"I want you to fix one of our miniature electronic direction finders somewhere on the man's body, where it cannot be discovered even if their greatest expert goes over him," Waverly told Dr. Morris.

The doctor examined the man's mouth. "We're in luck," be said. "He has a large filling in his lower right molar. We could take it out, insert the direction finder and re-fill the cavity," he suggested.

"Make sure the filling doesn't look new," warned Waverly. "I wouldn't want them to spot the direction finder by noticing a brand-new filling."

Dr. Morris looked at Waverly as if to say, "I don't need that kind of reminder," but only said: "It'll be carried out expertly. Don't worry."

"You spoke earlier of the possibility that a new dose of the poison might kill the man," Waverly said.

"Yes."

"If this happens, would a pathologist who has full knowledge of the poison be able to discover that the man had been given the poison again?"

"I'm sorry, but I can't answer that one. I haven't sufficient knowledge on how the poison works, nor how it affects the human body."

"Never mind," Waverly sighed. "As I said before, we have to take the risk of the man actually dying. I want the body to be ready for collection by the funeral directors in about an hour's time."

"Right," Dr. Morris acknowledged.

Waverly returned to his office to summon Illya Kuryakin and brief him on his new assignment. "I'll make the necessary arrangements for the City Funeral Directors to collect the body and I want you to take charge of the affair from then onwards," he said.

Two hours later, the funeral directors called at the U.N.C.L.E. office on the third floor of the whitestone to collect the body, and Illya was ready at his well-picked observation post when the closed van arrived and the coffin was carried into the funeral parlor.

Later, Illya stepped into a deserted doorway, took out his miniature shortwave transmitter-receiver, and said: "Open Channel D."

Within seconds, Waverly replied.

"A relative has claimed the body, sir," Illya reported.

"Arrangements have been made to fly the body tomorrow morning to Vienna, on the scheduled eight o'clock plane. I've booked a seat on it and will report from Vienna."

Channel D closed, and Alexander Waverly sat back in his chair.

CHAPTER FOUR

"DEAR DADDY––COME AT ONCE!"

THE Chief Organizing Officer at THRUSH'S European Center E made no attempt to conceal his anger. He ranted at the Chief of the Special Tasks Department for having given Vlasta Novak too much of the odorless gas.

"Almost twelve hours have elapsed since she was brought here and there's no hope of her regaining consciousness for hours yet!" he bellowed.

"How could anyone anticipate that she'd pass out so completely?" the Special Tasks Chief retorted, trying to justify his action.

"You know the strength of the gas, and you also know that once a person loses consciousness the supply must be stopped and fresh air allowed in to prevent over-doping!"

"How often must I repeat that we were unable to comply with the directions for the application of the gas?" the Special Tasks boss demanded. "I intercepted her at the Research Institute, told the story about her father's accident and offered to drive her to him. She was stunned but boarded the car. I was afraid she might turn awkward if I drove in the opposite direction to her father's villa, so I propelled a good whiff of the gas into the coupé to knock her out quickly."

"That's all well and good, but as soon as she'd passed out you should have opened the rear windows," countered the Chief Organizing Officer. "It only means pulling a lever."

"I've already told you that the electric window action wasn't working," the Special Tasks boss grunted. "And I also told you I couldn't risk stopping and opening the windows manually with the streets so full of people. Stopping, leaving the car and opening rear windows would have centered attention on me and the unconscious girl and might have endangered the whole operation. It's one of those unfortunate things, but the doctor should have brought her round long ago."

"The doctor made it perfectly clear that if he tried to revive her by drastic measures these could have fatal consequences. He should know—he's familiar with the effects of this gas, after all."

"Then there's nothing we can do but wait until she wakes. She can't sleep till doomsday."

"No, but time is precious. You know we need to get the Professor and his apparatus here as quickly as possible; and to do that without fuss and bother we need the assistance of his daughter."

At this moment the communication buzzer sounded. When the closed circuit television set was switched on, the Monitoring Officer appeared on the screen, to say:

"I've just received a message from New Yor

k, sir. It's short but satisfactory. Shall I send the tape to your office?"

"Play it back for me," the Chief Organizing Officer grunted.

A moment later the tape announced:

"Operation successful. Body claimed and arrangements for home burial made. Shall advise you after landing and European clearance."

"That's all, sir," the Monitoring Officer said.

"Thank you. Let me have the tape for filing."

"Very well, sir."

"Excellent news," the Chief of the Special Tasks Department exclaimed jubilantly. "This means 'Operation U.N.C.L.E. Headquarters' was carried out successfully and everything is set for the destruction of U.N.C.L.E."

"Yes, everything is ready for action, yet this Novak woman snores away merrily and delays our grabbing her father." The Chief Organizing Officer sighed at the dismal thought.

The Medical Officer had watched Vlasta from the moment she had been brought to THRUSH European Center E, and now he noted that the gas was beginning to lose its grip on her brain. "If these signs are not misleading, she should regain full consciousness fairly soon," he assured the Chief Organizing Officer through the telecomm.

"I'd better come round to the Medical Room to be there when she revives."

"I wouldn't advise it," the Medical Officer replied. "This gas has a peculiar effect on the brain. If anyone regaining consciousness is subjected to a shock of any sort there's a danger of complete insanity. That would knock your plans sideways."

"What do you suggest?"

"Leave her alone and let her come round gradually and undisturbed. Once she's her normal self, there's no danger of insanity and it's safe for you to see her."

"You mean you want to leave her to herself?"

"Yes, she must be left alone at first if the danger of possible shock is to be prevented."

"How will we know when she's ready for persuasion?"

"Oh, I'll be watching her continuously on the television screen in my office. Why not join me and watch her progress too?"

"I'll be with you presently," the Chief Organizing Officer replied.

Vlasta slowly came to. She felt terribly tired, her eyelids too heavy to open, with headache and dizziness upsetting her. As the effects of the gas diminished, her brain began to function normally and the tiredness and other symptoms slowly left her, until she drifted into a light, refreshing slumber.

"It won't be long now," said the Medical Officer, watching her on the television screen. "This light sleep will only last a short while, and then when she wakes she'll be normal."

Within half an hour, Vlasta opened her eyes, yawned and stretched. She sat up, looked around, and tried to puzzle out where she was.

"I'd better go in," the Chief Organizing Officer suggested.

"Not yet; there's still the possibility of shock," the Medical Officer warned him. "I'll see her first and condition her mind to her surroundings. It won't take long before you can step in."

He slipped into a doctor's white coat and entered the adjoining Medical Room.

"Oh, good," he said as he opened the door. "I'm happy to see you well again."

"What's happened to me, doctor?" Vlasta enquired.

"Don't you know?"

"Well, I remember having been told about father's accident as I left the Research Institute, and I remember boarding a car to be taken to him. Then I felt a choking sensation and wanted to wind down the window to let in some fresh air. I couldn't open the window because my arm and hand seemed useless—and that's the last thing I know. I must have lost consciousness."

"You did, Miss Novak," the doctor confirmed. "Fortunately the driver noticed your alarming condition in the driving mirror and brought you here. You arrived in time and the stomach pump and oxygen equipment saved you."

"What was the matter?"

"Food poisoning, Miss Novak, acute food poisoning. But that's over and done with now and you're back to normal."

"Acute food poisoning?" Vlasta exclaimed, surprised. "That doesn't make sense. How could I have got food poisoning? I had breakfast and lunch at the Research Institute and it tasted all right."

"One can't always judge from the taste of food whether it's all right or not, and apart from that, some people react worse to poisoning than others." The doctor sounded plausible.

"You ought to know," she succumbed.

"Yes."

"How is my father?"

"Oh, fine, fine. He's longing to see you as soon as possible—indeed, as soon as you want him to come."

"But he had an accident. Surely it's I who should go and see him?"

"The accident was really a false alarm. There's nothing to worry about. Your father is in perfect shape, but I'm afraid we can't release you yet because..."

"But you said earlier that the food poisoning was over and done with, and that I was back to normal," Vlasta interrupted. "If that's so there's no need for me to stay. I feel fine, really fine."

"Acute food poisoning and its aftereffects are not as simple as you think, Miss Novak. I repeat that the food poisoning is over and done with and you are back to normal, but I must add that in cases such as yours the patient must be kept under observation to detect whether there is any possibility of recurrence."

"All right then, doctor, you know best," Vlasta agreed. "When will it be possible for my father to come and see me?"

"I think you'd better discuss this with the gentleman who arranges this sort of thing—I'm only concerned with medical matters. He'll see you presently."

"Thank you, doctor."

The Medical Officer left to rejoin the Chief Organizing Officer. "She's all yours now. There's no longer any danger of shock and you can put her through the mill now, if need be."

As the Chief Organizing Officer entered, Vlasta looked up. She thought him quite good looking, though she disliked his thin lips and the close-set eyes which had a suggestion of cruelty. He noted that she was now looking very much prettier than before, when she had been under the influence of the gas.

"I am pleased to see you looking so well, Miss Novak," he said, and forced a smile.

"I feel fine," she replied, "and I think the doctor is being over-careful in keeping me here."

He ignored the remark. "I understand you're anxious to see your father," he said, sitting down on the chair beside the bed.

"I am, and I'm sure he's terribly worried about me, too."

"Well, all you need do is to write a note to him and I will arrange for him to be brought here immediately."

"I would rather phone him."

"That's not convenient," he said, dismissing her request. "You'll have to write a note."

"Can I have pen and paper?"

"Certainly." He gave the necessary orders to a messenger outside and the pen and paper was quickly brought to her.

"A short note should do," he suggested. "And you can tell your father that he can bring along his apparatus, if he wishes."

"How do you know about that?" Vlasta exclaimed, suddenly alarmed.

"My dear Miss Novak, you talked almost non-stop about your father's apparatus and your assisting him while you were unconscious," he lied. "So you see, I am only trying to be helpful—both to your father and you—by giving you the opportunity to utilize your stay here to continue working on 'Project I.P.' With a project as important as that, there is no time to lose, for the sake of the world and humanity. It's a wonderful idea."

For some inexplicable reason Vlasta began to feel uneasy. She asked: "Which hospital am I in, actually?"

"This is not a hospital," he told her. "You're in the Medical Room of an organization."

"I want to leave at once!" she demanded, as she suddenly sensed danger.

"I'm afraid that's not possible," he said suavely.

"Are you saying I am your prisoner?"

"Let's say, a guest—as long as you don't behave foolishly."

There was now an expression in his eyes she didn't like, yet she was not afraid, and was determined to with

stand any pressure on her.

"I'd advise you to write the note, Miss Novak," he pressed. "It would make matters very much easier all round."

"I am not going to write anything. I am not going to help you get my father here!" She was adamant, despite his threatening tone.

"You have five minutes to change your mind. If you..."

"I am not going to change my mind in five minutes or five thousand hours," Vlasta interrupted.

He stabbed a button on the wall beside her and seconds later two guards and some THRUSH officers filed into the room. Vlasta was securely strapped to the bed and electronic equipment was attached to her limbs.

The brainwashing and conditioning of her mind lasted a considerable time. When it was done, she wrote the note to her father.

His daughter's disappearance had brought Professor Novak to the verge of a nervous breakdown. He had visibly aged, and felt physically ill. He couldn't sleep, didn't touch food or drink—only chain-smoked. He was almost continuously in touch with State Security Headquarters, but the people there could only repeatedly tell him that the nationwide search for his daughter had not been slackened for an instant. As the hours dragged on without the slightest clue being found, he lived in fear that he would never see Vlasta again.

The stillness of his villa was suddenly disturbed by the sound of the doorbell, but he was not interested in learning who his visitor was, being in no mood for seeing anyone. All he wanted was news that his daughter had been found alive, and that, he knew, could only come by telephone from State Security Headquarters.

The caller continued to ring the doorbell.

Grudgingly the scientist pulled himself from his arm chair in the living room and walked heavily to the entrance door. When he opened it, a stranger, a well-dressed man of about forty, raised his bat and said:

"Professor Novak?"

"Yes."

"May I come in, please?"

"What is it about?"

The Thinking Machine Affair

The Thinking Machine Affair